Although bullockies were popularly perceived as figures of fun and

ridicule, of appallingly obscene language, and notoriously dissolute habits,

they performed an essential service in the early days of the colony.

|

| Unloading a Bullock Wagon |

Until the coming of the railway in the 1860s, the wool from the vast

sheep runs of the Darling Downs and the districts below the Range was

transported to Ipswich by bullock drays.

Travelling over rough country and unmade roads, bullocks were much more

proficient draught animals than horses.

Before the railway, Ipswich was a busy river port as it lay at the

farthest navigable point inland. A wharf and warehouse was soon built to

accommodate the river steamers.

|

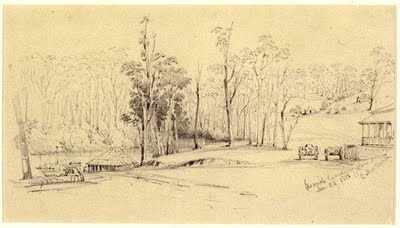

| Ipswich landing place Nov 24, 1851 (Conrad Martens) |

As a result the streets of Ipswich were lined with bullock wagons

bringing in bales of wool and waiting for return loads of various goods and

supplies for the sheep stations. During

the layover, the bullockies enjoyed the hospitality of the local public houses

and the charms of the ladies of “ill repute”.

A well-known bullocky character familiar to the residents of Ipswich

was known by the curious nickname of “McGouzlem's fool”[1]. He was also a frequent guest of the

constabulary.

|

| Bullocky standing with his whip and bullock team at Rosewood c.1882 |

The sittings of the Ipswich Court in 1849

saw the usual parade of misbehaving bullockies.

First to appear was one William Smith on a charge of indulging in the

use of obscene language. The magistrates were making use of the new Vagrant

Act.

William Smith, bullock driver to Mr. C. W. Pitts, was

brought up for using blasphemous language in the streets. The charge was fully

proved, but as this was the first case under the new Act, which was not perhaps

generally known amongst the working classes, their Worships fined the defendant

only one shilling, at the same time admonished Smith, and directed him to

spread the news far and near, especially amongst his "mates of the

whip," whose propensities in this unfortunate failing are proverbial.[2]

|

| Bullock Driver Brandishing his Long-handled Whip |

Next to front the court was a colleague of Smith, one Thomas Milner,

popularly known about the streets of Ipswich as “McGouzlem's fool”. The Ipswich Correspondent of The Moreton Bay Courier took great

delight in describing his appearance and his dialogue with the magistrates.

Next appeared, for the same offence, and also

drunkenness, a mate of the former defendant, named Thomas Milner, better known

as McGouzlem's fool, a regular Victor Hugo's "Quasimodo"[3]

in ugliness, whose entree created much mirth.

He was indeed as ugly as sin, with an obliquity of mug

truly remarkable, and lips that would rival any Hottentot[4]

Venus, beard of at least a week's growth, manured by a portion of some puddle

which his phiz[5]

often appears to fondle,- and hair of "mud coloured grey," standing

out like quills upon the fretful porcupine. Fancy all this, and you have my

"Caliban"[6].[7]

Their Worships struggled to maintain their serious demeanour as the

following exchange proceeded.

The subject matter in dispute will be seen by the

following colloquy between Bench and defendant -

Bench - Were you drunk?

Defendant - Oh! yes.

Bench - How much did you drink?

Defendant (grinning most ominously) - Until I got drunk.

Bench - Had you no water to wash your face?

Defendant (another grin) - I forgot the water while I

drank the rum.

During this short confab the calcinatory muscles of the

auditors were exercised to an unusual degree; even the stern front of Justice

was compelled to relax, which was perhaps so much in favour of McGouzlem's

fool, that he was only admonished as to the present working of the Vagrant Act,

and fined five bob.[8]

This would not be the last time McGouzlem would appear in the Court

reports, but by all accounts he was a likeable, harmless character who was fond

of children.

|

| Bullock Wagon in front of Cribb and Foote London Stores, Bell Street, Ipswich, 1850s-1860s |

© K. C. Sbeghen, 2012.

[1] Of

obscure origin.

[2]

The Moreton Bay Courier Monday 10

December 1849

[3]

i.e. “The Hunchback of Notre Dame”

[4] A

derogatory term for an uncivilised, primitive “native”.

[5] face

or facial expression (OED)

[6] A

man of degraded bestial nature (a character in Shakespeare's Tempest)

[7] The Moreton Bay Courier Monday 10

December 1849

[8] The Moreton Bay Courier Monday 10

December 1849